Hirschfeld and M. Butterfly

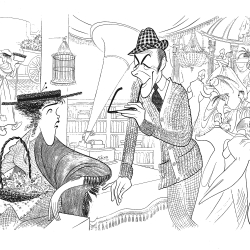

With the revival of M. Butterfly to soon open on Broadway, we decided to look back on Hirscheld’s drawings of the original production almost thirty years ago. This is adapted from The Hirschfeld Century: A Portrait of An Artist and His Age (Knopf, 2015)

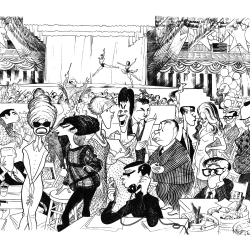

Hirschfeld’s Sunday drawings, often splashed across the top of the fold of the “Arts and Leisure” section of The New York Times, and which were usually cast composites contrasted with his “Friday” drawings for the Times’ theater column. These weekly works were the laboratory for Al to explore what he could do with line. Focusing on one performer in a single show, and for a very small space, pushed him to refine his work even more. Forced by the space constraints he literally had to make every line count. He purged these drawings of all extraneous pictorial detail, leaving almost only the most essential elements for the composition, and recognition.

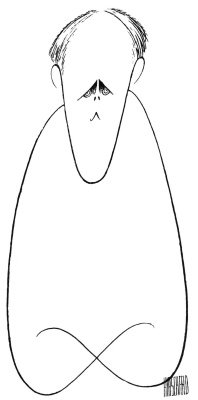

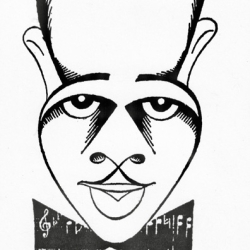

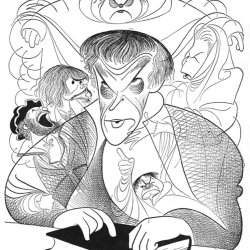

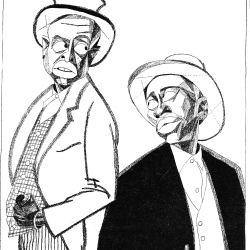

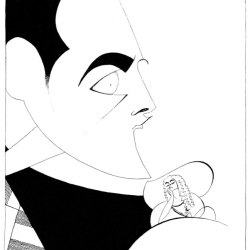

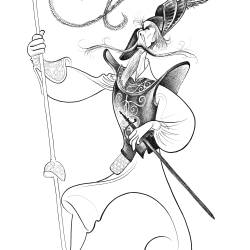

His 1988 drawing of John Lithgow in M. Butterfly is a perfect example of how he eliminated all but the most necessary elements, creating not only a stunning picture, but a great portrayal of the actor in the role. Al draws Lithgow’s head as elongated egg, and puts in sullen eyes, two dots for a nose and an inverted “v” for a mouth. Lithgow looks like the unhappy French diplomat who falls in love with a Chinese opera diva who turns out to be a man. Besides a slight suggestion of hair, the only other lines are the two that are his arms and hands, although neither are shown in any detail. Upon seeing this work in an exhibition the following year at Harvard, Boston Globe art critic Robert Taylor explained how Al “deploy[ed] white paper as a support for a breathtaking line that swoops, curls and spins, often in a single continuous stroke. The masters of Chinese and Japanese ink brush paintings practiced the same intense gestural economy, the same winnowing of the extraneous to enhance their line’s dramatic swell and fall…[the] line itself assumes center stage, and actor of authoritative powers in a classic role.”

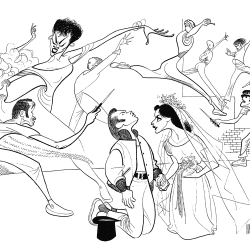

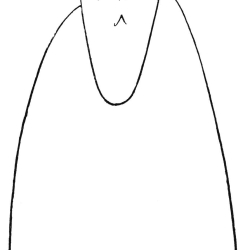

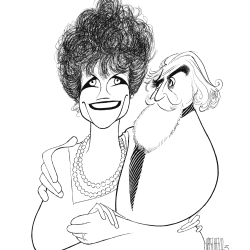

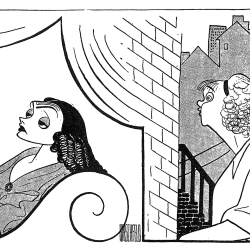

Four months after the Lithgow drawing on a Friday in September 1988, Al drew B. D. Wong as Song Liling, the diva at the center of the play, in a style that clearly acknowledged the calligraphic works that Taylor alludes to. When this drawing was later published as a limited edition lithograph, Hirschfeld extended the homage by printing the work on a type of Japanese rice paper, adding faint flat color, much like the works of Hokusai and Utamaro he had long admired.