What Happened in 1971

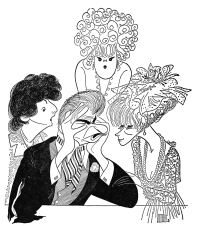

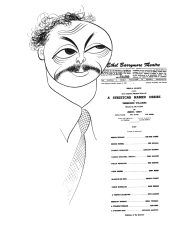

A collector commissions a series of drawings of Pulitzer Prize-winning plays and separate portraits of their authors. Hirschfeld creates five of each including You Can't Take It With You, A Streetcar Named Desire, and Death of A Saleman before the collector runs out of wall space.

He draws the "Counter Culture at Zabars."

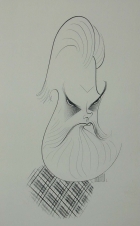

For the New York Times Op Ed page, Hirschfeld draws V. Thant, Chief Justice Warren E. Burger, and Mao.

Drawings of television productions include Paradise Lost with Eli Wallach and Jo Van Fleet, The David Frost Show, Jane Eyre with Susannah York and George C. Scott, The Winds of Kitty Hawk, and a Gershwin special.

Films drawings include McCabe and Mrs. Miller, The Boyfriend, Carnal Knowledge, The Go-Between, Fiddler on the Roof, and a portrait of Robert Mitchum.

Hirschfeld draws the cover of The Collected Dorothy Parker.

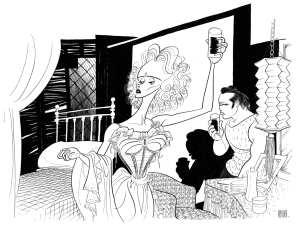

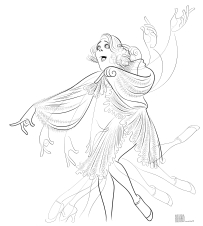

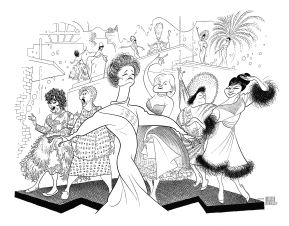

His theatre drawings include Little Murders, All Over, How the Other Half Loves, Plaza Suite, Jesus Christ Superstar, The Prisoner of Second Avenue, Two Gentlemen of Verona, and Ruby Keeler in No, No Nanette.

Decade: 1970

…But pouf, you exclaim, impatient with externals and avid for a clue to his extraordinary graphic talent: whence does Hirschfeld derive his technical skill, his ability to compress into a few slashing lines the quintessence of his subject? As to that, nobody can really say with authority, but there are a couple of possibilities. To begin with, Hirschfeld’s exact age is a matter of speculation. The municipal records in St. Louis give his birth date as January 18, 1963, which is ridiculous; a ten-year-old boy does not have flat feet and a patriarchal white beard, and furthermore, how account for a flop musical comedy he and I collaborated on more than a quarter a century ago? (A question also asked by drama critics at the time.) In seeking to elucidate his facility with the pen, therefore, we must fall back on hypothesis. To mention but one theory, it is a well-known around Broadway that Irving Berlin plays the piano with only one finger and relies on a small colored boy, a brilliant musician, to orchestrate his songs. What is no so well-known is that this pickaninny is also a brilliant caricaturist. Could it be that he furnishes the basic or primary sketches to Hirschfeld, who merely inks them in? I have, in fact, insinuated as much to the latter on occasion, but his sole reaction was a sphinxlike smile…

The other, or geriatric, conjecture is one I would normally hesitate to accept, but studies of longevity in Ecuador, Soviet Georgia, and Hunza in northwestern Pakistan tend to support it. Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, the famed French painter and draftsman, allegedly died in 1867 at the age of 80. I repeat ‘allegedly,’ since as we all know, the Franco-Prussian War was brewing, everybody was running around in circles, and vital statistics often were lost or distorted. Suppose, then, that Ingres didn’t actually die but slipped out of France during the turmoil. Now, where would one go if he was an old Frenchman searching for a secure and peaceful existence? Obivously to some place like St. Louis, a city founded by his countrymen on the Mississippi with extensive levees (Ingres loved levees), and colorful natives strumming banjos, courting and dancing the cakewalk. And just suppose – stay with me a minute — suppose that by sheer happenstance he bumped into the Hirschfeld clan out there, warm-hearted people that took pity on this homeless old foreigner, not knowing his age or the first thing about him, and they adopted him, reared him as one of their own children…You see what I’m driving at? Simply that if Hirschfeld draws like a streak –which he does, yes, yes, enough already — it’s no wonder. So would you if you were Jean Auguste Dominque Ingres and you had 193 years of practice. I don’t know why everybody’s making such a fuss over him. To me he’s just a fat little dwarf with whom I once wrote a flop musical comedy.

“The Flash” by S.J. Perleman, ART News April 1973